Issues with 1950s Payment Cards

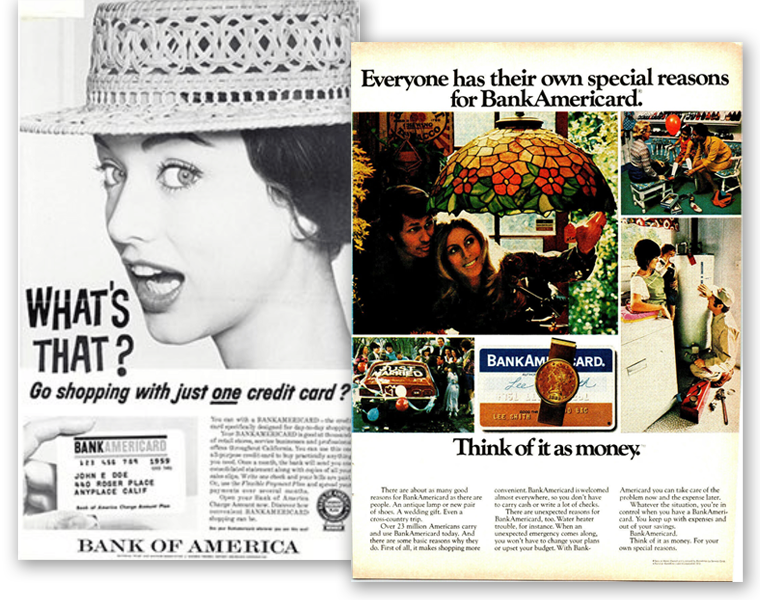

Since the creation of the first payment card by the Diners Club in 1950, other merchants around America have started creating charge cards where consumers can bill their purchases to an account to be settled by the end of a set period, usually at the end of the month.

However, only small networks of specific retailers accepted these cards such as restaurants (that sparked the initial idea for Diners Club) or department stores. Each transaction required time-consuming account referencing and tedious bookkeeping. On top of that, if the customers failed to settle their accounts at the end of the month, it was the merchants who have to bear all the costs.

Dozens of small American banks have attempted to create a general-purpose card catering to the masses, but none of them lasted. There was a catch-22 situation in which consumers did not want to use a card that only a few merchants would accept, and merchants did not want to accept a card that only few consumers used.

That was until the Bank of America finally found a way to solve this problem with a radical experiment.

The Fresno Drop – The Birthplace of Revolving Credit Cards

To solve the chicken-and-egg dilemma that other banks have been facing, the Bank of America knew that it needed customer base large enough to solve one side of the problem, but small enough to minimise cost and media attention if it failed. Fresno was a remote city with population of around 250,000 and since 45% of Fresno families were already the bank’s client, it was an excellent test market for their first credit card.

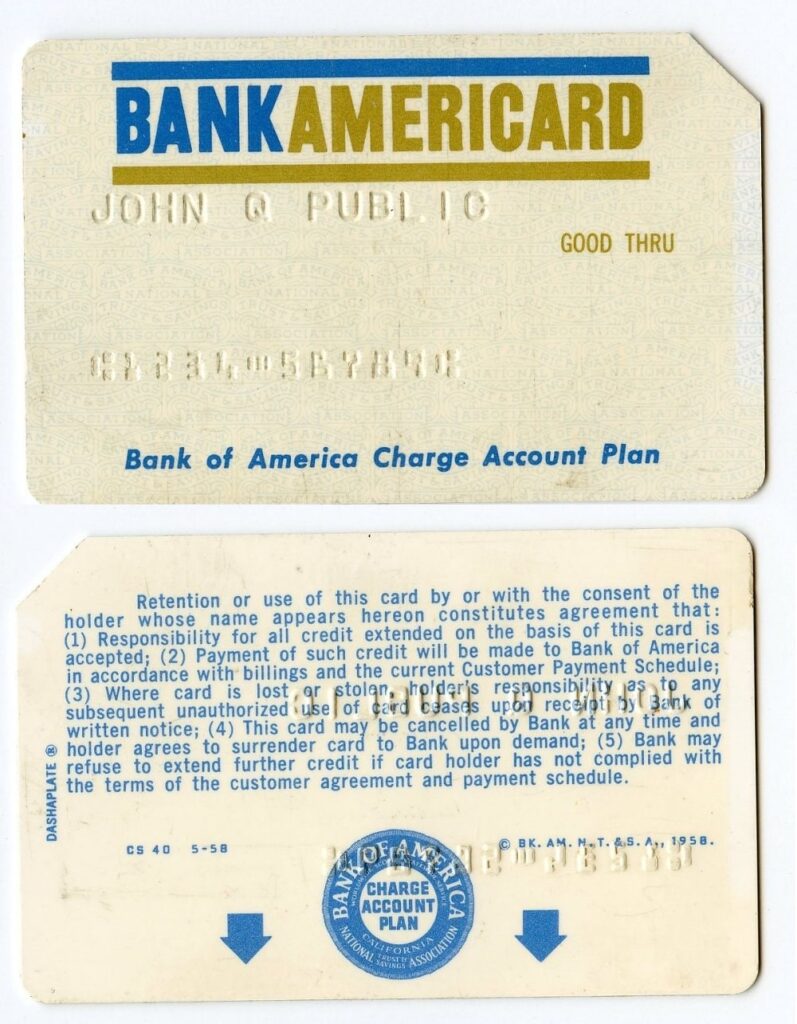

So, in September 1958, the Bank of America dropped a small plastic card with the word “BankAmericard” printed on the front into the mailboxes of 60,000 households with no warning, no credit requirement. Just a note with a US$300 – US$500 credit on the card for consumers to use and pay the bank back at any time.

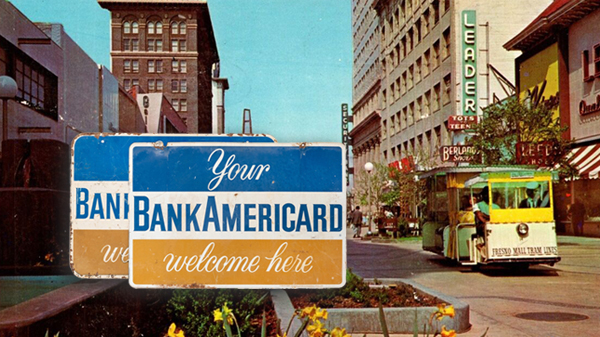

With tens of millions of dollars suddenly flushing into the Fresno economy, local merchants had to accept the BankAmericard or lose out on all the business. Plus, this would save the merchants’ headache and costs of account keeping including labour, postage, and bad debt! The bank focused on signing up small merchants rather than retail giants and recruited more than 300 merchants by the time of the launch.

The Challenges and Solutions

A few months into the test period, another competitor was planning to issue similar card products which prompted Bank of America to react and mail out a total of 1 million pre-approved working credit cards across California within 10 months. As you can probably imagine, chaos ensued. There were high levels of fraud, a delinquency rate of over 20%, and theft of credit cards from the post which eventually led to a loss of US$20 million (equivalent to $218 million today) in the first year!

This, of course, caught Bank of America by surprise as their customers were mostly from stable income households and had been good with repaying home loans with a low delinquency rate of only 4%.

Thankfully, the Bank of America persisted on improving the program by investing in security features and involving the loan manager (who wasn’t initially involved in the roll out) to implement stricter policies, creating the Collections Department and Anti-Fraud unit. Eventually, the bank started to profit from the program and began to make millions annually a few years down the line.

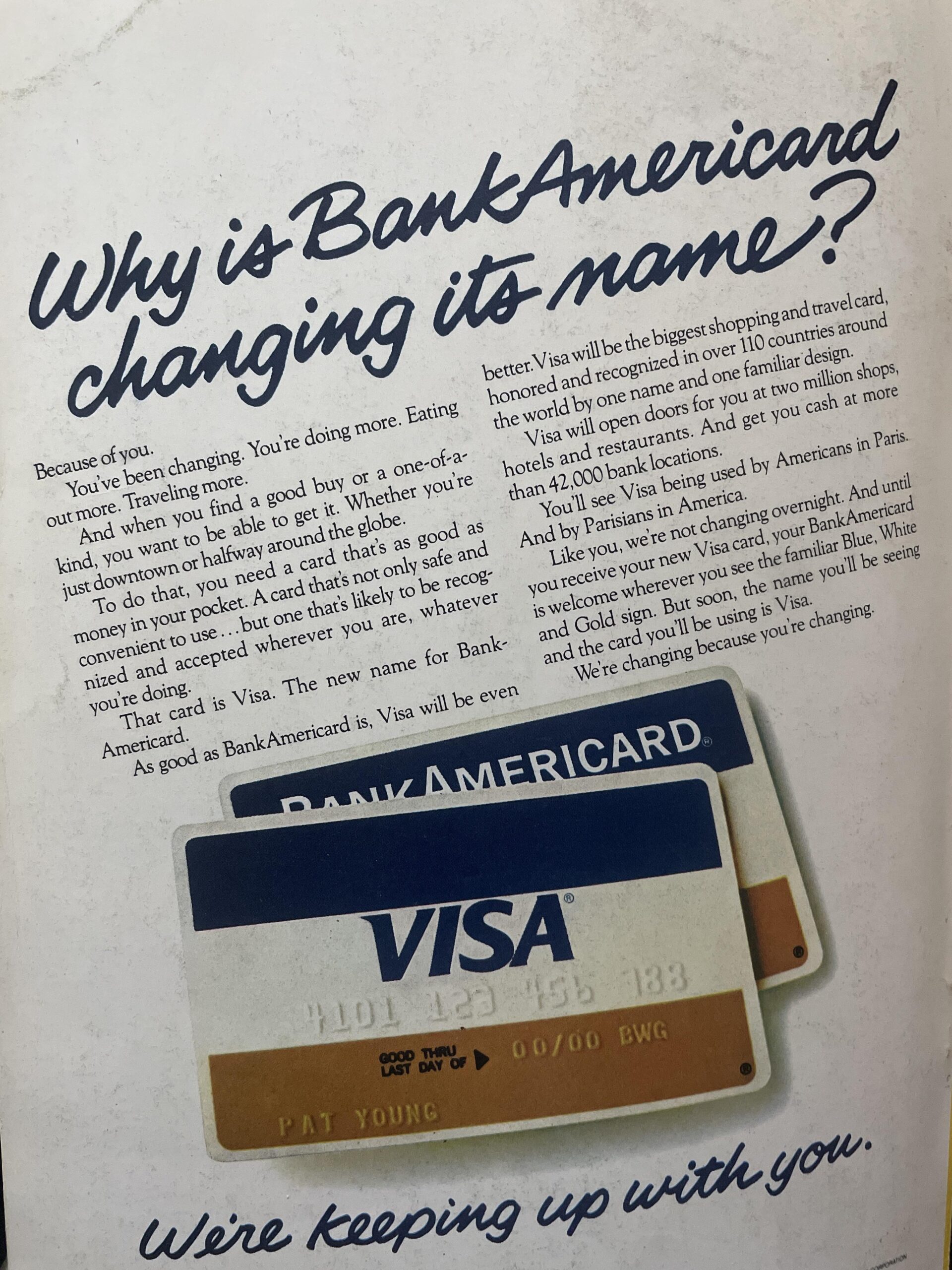

BankAmericard's Evolution into Visa

Needless to say, other banks quickly copied the model. Some banks and regional bankcard associations consolidated to form Master Charge (now MasterCard) to compete. This lead Bank of America to license the BankAmericard program to other financial institutions in 1966 which eventually became Visa in 1976, one of the largest credit card processing networks in the world today.

Hence, the model of universally accepted revolving credit was born. The initial Fresno drop may have been a bit of a chaos to begin with, however, it was a revolutionary risk that paved the way for the payments industry.